Hello, everyone. Super excited to be here again with Dr. Satchin Panda, who is a professor at the Salk Institute for Biological Science. And this is actually a round two podcast. Previously Satchin and I had a really long and interesting discussion on his research and how…we talked a lot about how the body’s internal clock, which is known as the circadian rhythm, how that is regulated by the external cues, such as light, and how the interaction between light in a certain part of the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus.

Which is like the master oscillator, as it’s called, or master regulator, of circadian rhythm and how circadian rhythm regulates, you know, when we’re active, when we sleep, when we’re awake, when we eat, things like that. But also we talked a lot about this other external cue which also regulates circadian rhythm in what’s known as peripheral oscillators. Which are other tissues outside of the nervous system, such as the liver and the gut, and how that’s actually regulated by the timing of the food that we take in. And that’s where Dr. Panda’s work comes in, has shed a lot of light on what this…what’s called the timing of the food intake and how restricting that timing of your food intake to a certain period of time, for example 9 to 12 hours during the day, can possibly affect a variety of different metabolic outcomes and health factors.

So his research in animals has shown that animals that are restricted to eating within a 9 to 12-hour window have improved glucose metabolism, improved lipid profiles, improved cholesterol, you know, increased lean muscle mass, decreased fat mass, decreased fatty liver, you know, favorable gene expression patterns, all sorts of, you know, really favorable outcomes. In addition he’s also shown that when these mice are fed a…what would be sort of analogous to, I think, the standard American diet, which is, like, high in sugar, high in saturated fat, just not a really good diet.

If they are restricted to this narrow timing, you know, feeding window, which is 9 to 12 hours, they still have improved markers of metabolism and metabolic function. Which is really hopefully in a way because I think it also indicates that there may be some possibility that for people that have a really hard time eating healthy or just don’t eat healthy, maybe even just doing this one thing where they… I mean obviously we want them to eat healthy. But if they don’t, eat within a certain time window that’s more restricted possibly that would have favorable outcomes. So I’m super excited, Dr. Panda, or Satchin. So just sort of since we’re talking about this, do we have any human evidence that the people that have, for example, like metabolic syndrome, if they eat within a time-restricted eating window, there’s any benefits to that without changing their food composition? Well, historically most of these research studies haven’t looked at timing per se, but there was a very nice, comprehensive review published by American Heart Association that went back to many studies where timing, or at least how many times people ate during the day, was recorded.

And after compiling all the studies, it was close to 70 or 80 different studies related to fasting of decent quality, how many times people ate, that found that, yes, limiting food to a certain number of hours during the day or maintaining overnight fasting was beneficial for cardiovascular health. So that’s a very well done meta-review of existing literature. What we need to do now is to look for new studies where this is specifically looked at where everything else is kept constant and timing is changed so that we’ll see whether the benefit is seen among individuals who already have metabolic syndrome. So that’s what is lacking in the field. And, as you know, this is a very new area of research and NIH funding cycle is five years, so any of the studies will take at least five to seven years before we see any result and peer-reviewed journals.

Particular for, I guess, a clinical trial of actually looking at someone with metabolic syndrome. Probably obesity… I mean if a person is obese, it may take a little more than just time-restricted eating to lose weight. Although they may, they may lose some. They may require more of a, like, prolonged sort of fasting, but the time-restricted eating certainly would affect their… I would predict would affect their metabolism. Yeah. So what we see in our study, a small study that was published, and also some of the other studies that may be in the pipeline, when people adopt a time-restricted feeding in their regular life, in real life, not in the laboratory condition or in clinical trial, then they naturally reduce their caloric intake without even counting calories.

So, for example, when they stop, suppose their target to stop around 6:00, 7:00, or 8:00 in the evening, then the late night snacks and then the late night glass of wine or beer that used to be their usual habit, they stop that. So in that way they’re doing two things, one is reducing calories and also improving nutrition quality because that extra energy-dense diet is not getting into their system. So in that way I’m hopeful that we’ll see some weight loss, and then some improvement in real health, blood biomarkers. And in rodent studies what we have seen when we take already fat mice, who have been eating a really unhealthy diet for a long period in their life, and then put them on a time-restricted feeding paradigm, they don’t become, like, lean mice in terms of body weight. They become overweight, not normal. But surprisingly they’re biochemically…or physiologically they’re more healthy because their blood biomarkers for glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides, they come to almost normal range.

So we have to make the distinction that some people may not lose a huge amount of weight, but they might actually see benefits in their metabolism and physiology. So that’s one thing you have to look out for. But this is, the mouse study you were just referring to, they were still fed a poor diet? Isocaloric. Yeah, okay.

Yeah, they were still fed a poor diet, isocaloric diet. So imagine if they were fed a better diet and…the obese mice were fed a better diet and they were doing time-restricted eating. Yeah, so they would be much better. Much better. They would lose more fat mass and become much more healthier. Can you explain for people who just aren’t very familiar with time-restricted eating or time-restricted feeding, as we call it with animal research, like, just what is that and how does that actually affect your metabolism of glucose and fatty acids and amino acids? Yeah, so let’s kind of step back and ask how does it relate to circadian rhythm, or the daily rhythms.

So if we think of our daily health, our health, our personal sense of how we feel healthy changes from time to time throughout the day. So, for example, in the morning when we wake up, being healthy means you’re feeling much rested and you’re full of energy to start the new day. You’re feeling actually much lighter, you should not feel that full stomach or grogginess, and have a good bowel movement. And then throughout the day being healthy means not feeling too hungry, so having some food in your system, and then being productive throughout the day. And then towards the end of the day being healthy actually means having taken a walk or something so you are not feeling really…you haven’t moved all day and you’re not feeling that sense of being constrained in a place. And at night time before going to bed being healthy means feeling really sleepy, so that as soon as we switch off the light and get into the bed we fall asleep. So in this way you can see that being healthy, this definition is very different at different times of the day.

And a lot of it actually has to do with physiology or metabolism. So in the morning feeling lighter and not groggy and not having a food hangover means you have already gone through…hopefully somebody has gone through 10 to 12 or even 14 hours of fasting, not having food in the system, so that your body has metabolized all the food and has processed it and your gut has also gone through rest. And then towards the end of the day when you’re going to hit the bed, if we have food in our system, what happens is blood flow is directed towards our stomach to digest the food and absorb it, so core body temperature remains high.

So not having food for two to three hours before going to bed actually helps us to go have that deep sleep, sound sleep throughout the night. So in this way now if we back up and think, “Okay, so when should we eat?,” then it makes sense that, well, after waking up maybe give one or two hours before we start eating, and then before going to bed at least three to four. Depending on what your metabolism, two to four hours before going to bed we should stop eating. So that brings up an eating window of, say, up to 10 to 12 hours max when we should be eating so that we have that personal sense of being healthy throughout the 24 hours. So in animal studies what we have done is we ask a very simple question. If we take animals and give them food just like most labs do, they have food in the hopper they can eat whenever they want, and we calculate how many calories they eat. And then we take another group of mice and then give them the same number of calories and from the same source of food, whether it’s high carb, high fat, high fructose.

It doesn’t matter, we have to give the same source of food, same number of calories to the second group. And they have to eat all that food within 8, 9, 10, or even 12 hours. Then we consistently find that the mice that eat all their food within this 8 to 12 hours window are healthier than ad libitum fed mice. So that led to the term, what we call time-restricted feeding, where the timing of food when we eat is restricted or you define it and stick within it. Not caloric restriction, where you have to count calories and restrict it. So in this way it becomes very easier because you just have to…we all know how to manage our time, on a daily basis we are always dealing with time. So it becomes easier because if we start eating around, say, 8:00 in the morning and, based on our lifestyle, we can do 10 hours eating, then I’ll have my dinner, say, around 6:00. So that’s the concept of time-restricted eating or time-restricted feeding. And, yeah, I think that having the time where you just sort of say, “Well, I should stop eating by, you know, 6:00,” or, you know, kind of having it so you don’t have to constantly each day think about it, like, “When did I eat my first meal?,” or,” When did I take my first bite?” If you kind of just have this general schedule where it’s, at least during the workweek, you know, it’s easier.

And then another thing I must point out, that in our animal experiments, when we do these experiments, suppose we say eight hours, we’ve fed the animals for eight hours. And then every week we measure their food intake and some weeks they might eat less. And then we immediately change that schedule to, say, eight and a half hours or nine hours the next week to make sure that they actually eat the same number of calories. So moving this needle by one hour actually is not that detrimental. It still gives them the benefit. And we have also asked another question, so in animal experiments. In weekend we let them free, they can eat whenever they want. And they definitely go outside of a 12-hour window, they eat almost throughout the night. But still that two days of binge eating can be counteracted by if they stick to 8 to 9 or 10 hours during the weekdays. So that also gives us hope that perhaps in humans occasional eating maybe once or maybe maximum twice a week can still be tolerated. That’s good to know, I guess a lot of people would be happy to hear that.

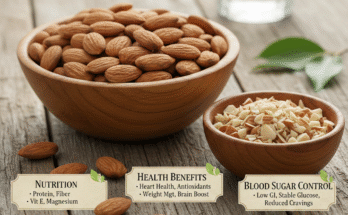

Yeah. What do you do? So for your typical workweek and then weekend schedule, like, what’s your time eating window? Yeah, so it’s… You know, I travel a lot, too, but I…what I’ve found is if I stick to maximum 12 hours window, then I actually feel much better and more energetically, I sleep well, and I feel lighter, and I’m still productive throughout the day. So I start, say, somewhere around 7:00 or 8:00 in the morning, and then I stop around 5:00 or 6:00 in the evening. And I also try with different types of diet once in a while. One thing with many people who are new to time-restricted eating, or eating or feeding, is when they start it they feel hungry. And what we have found is while having a fiber-rich diet or a protein-rich diet or a slightly higher fat-rich diet actually helps to go through that longer time without food.

And slowly you also get used to it. And all of these actually increase your nutrition quality because you’re staying away from simple sugar and high glycemic food and you’re leaning more towards food that takes a longer time to digest or longer time to absorb. So that helps. And that way my diet, both diet quality and also the duration have changed. And I usually stick to 12 hours, and in many cases I kind of try to stick to 10 hours.

Oh, me, too. I try to stick to 10. You’re talking about the people feeling hungry when they first try this out. Has anyone ever looked at how time-restricted eating affects satiety hormones, like leptin or ghrelin, which would be the one that makes you hungry? Yeah, so we haven’t looked at that in humans, but in mice what we see is all of these hormone levels that come back to more homeostatic range, that means they don’t go too high and also don’t go to low.

So that was kind of surprising because we thought that the hunger level will go up and the hunger hormones might go through the roof. But somehow after a few days the body adjusts to it, and then it gets them in a homeostatic range. And also humans who do it, we do see that after two to three weeks the hunger at bedtime is pretty low. They don’t feel hungry. They might feel actually lighter and ready to sleep. So then they realize how it feels like to go to bed with a lighter stomach than with a heavier stomach.

Yeah. And then once you actually, if you break that time-restricted, you know, eating or feeding window, I’ve noticed at least in myself you actually start to feel worse. Yeah, yeah. Like right now I’m 37 weeks pregnant and through my pregnancy I’ve pretty much thrown, you know, my TRE and my time-restricted eating out the window. Well, I do do 12 hours, but usually I do 10, I try to do 10, sometimes 9. Particular if I’m going to go for, like, a run in the morning or something that’s endurance-related, I like to eat within a shorter time window. Yeah. But there are times that I can’t even do…like there have been time throughout my pregnancy that I can’t even do 12 hours and I eat a little bit after that.

And I do notice it affects how I feel. Yeah. Like I feel more lethargic the next morning. Yeah. So there’s this food hangover that stays with you. It’s almost like, yeah, as if the food stayed there in the stomach, it didn’t get digested, or the stomach was sleeping when the food came. Right. And we get that response from many of our users, app users, that do say… From myCircadianClock. myCircadianClock app. There are many times when people… Usually what happens is for the first two to three weeks people are very diligent, they try to do it and they get into that rhythm. And then we get this occasional feedback. Around week five or six when occasionally they felt like they could go out late at night and eat, and then the next morning they felt horrible because they were feeling so lethargic, so groggy. And then they e-mail us saying, “Wow, really it felt like our stomach was really sleeping and I’m not going to do that again.” That’s interesting.

So it’s kind of interesting that that hits around week five, six, seven when people think that they have adapted to a lifestyle and they are doing okay and maybe they can occasionally east outside the window. And they do that late into the night, and then the body reacts. Yeah. And they recognize that reaction. So for people that aren’t familiar, the myCircadianClock app can be found on the website myCircadianClock. And it’s basically you’re crowdsourcing data. You know, people that want to try this time-restricted eating out can try it out and also send their data to you and take pictures of their food so that you can gather data for your study, yeah. So that’s kind of a neat thing, that people can participate.

While they’re trying this out, why not contribute to science? Yeah. I mean what we realized is even if we get the best funded clinical trial grant from NIH or DoD or any funding source, most of the clinical studies are done with people who live within 20 to 30 miles radius of a clinical center. And so in that way, even if we foresee there will be five or six clinical trials in this country, there will be only five or six of those centers. And people who are living within that 20 to 30 miles and have time and energy to travel to a clinical center, spend almost half a day and every two to three months or two to three weeks will participate in this study and will see the benefit firsthand.

Then we realized that in that way most clinical trials which are low risk like this one actually will benefit…or will sample a very small fraction of people. So that’s why I came up with this idea that if we have a study that’s approved by our ethics committee and we make sure that we maintain the privacy of people, we don’t sell this data, we don’t share this data with anybody else, and we give that assurance up front, then we may be able to recruit or enlist participants who are not living within 40 miles who don’t have time to come to a clinical center, but are willing to share their data for science. And they can live anywhere in the world, they can share their data.

And in this way this has been extremely useful because, again, in any clinical trial if you look at the exclusion criteria, there is such a long exclusion criteria that only 1 in 50 or 1 in 100 who even shows interest in participating, they can participate. But if we take that result and then try to disseminate to the rest of the people, those 49 or 99 people who could not qualify, then how are we expecting that this would be applicable to all of them? So it’s kind of a conundrum. So that’s why we thought let’s try this way where the only exclusion criteria is if you are below 21 because that’s NIH’s mandatory exclusion criteria. And in this way not only we can see whom it will benefit, we may also see whom it will not benefit. So we can actually a priori figure out what are the limitations of TRE. And people who don’t qualify, for example shift workers, they’re mostly excluded from many clinical studies because of the nature of their work, they cannot come to the clinic at the right time, and this is more relevant to them. So now we have thousands of people who are shift workers and they’re trying this.

And from them we are also learning what they can adapt and how they can adapt this TRE into their lifestyle and whether it helps them with alertness being on the job and whether it helps them to sleep on the weekend and all that stuff. So that way this has been extremely useful to have this kind of study and sometimes we even get responses from our users that we had never thought about. So we take that response and see, “Hey, can we do this animal study and see what is going on? What is the biochemical basis for this? What is the physiological response in animals?” Maybe that’s how we can address…

For example, there are many cases there are many immune-related diseases and people report that this immune-related disease has improved on the time-restricted eating. And that is surprising for us. But then we went back to our animal data and we realized that, yes, we actually see systemic inflammation goes down with time-restricted eating. And that makes sense. If the systemic inflammation goes down, then many immune-related or inflammation-related diseases would also go down with time-restricted eating. So there are some examples like this where our human participants tell us their story.

And if it is one or two person, we may not take it seriously. But then it’s 4 or 5 or 10 or 15 people telling us the same kind of story. For example, many IBS patients who have irritable bowel syndrome who have been going to the toilet for five, six, seven, eight times every day. They do TRE, and then they immediately see that the number of times they go to the bathroom has gone down. It’s a huge improvement for them. And then we might hear this story once or twice, we may not take it seriously. But then if we hear it 5, 6, 7 times, then we start thinking, “Okay, let’s go back to our animal data.” Because from all these animals we have collected every tissue that’s imaginable and we have a freezer full of tissues. And then we go back and test what might have changed, what might be changing in the gut, what might be changing in the intestine, did the microbiome change, did the interaction between the microbiome and the horse change.

And that helps us to come up with newer hypotheses and do more focused studies. So this has been extremely useful for people to go sign up on the myCircadianClock website, and then download the app and share their data and also share their experience. Wow. I just love hearing…there’s so many things that you brought up that I have marked in my head to talk about. But first of all, to speak to your point, this is really… I think it is extremely important that you’re gathering all this data from people without all these limitations, aside from the age limitation. Like you said, you’re getting the shift workers. I mean this is hugely relevant for shift work and, you know, people that have IBS, people that have, you know, multiple sclerosis.

Obviously people that have certain conditions are probably consulting with their physician. Yeah, they do. But, still, you’re getting this data, and then seeing these trends when people start to say these things over and over. Like, “Oh, my IBS is improving.” And you hear it five, six times, then you start to go to the mouse data and start to do experiments and tease our mechanisms. Yeah. I mean it’s just fantastic, it’s absolutely fantastic. So the first thing with inflammation you mentioned, do you think that part of the reduced systemic inflammation has to do with the fact that, you know, if you’re eating within the time-restricted window… And this is something, you know, your metabolism is optimal during this certain time window. So the first time you take in food sort of starts these peripheral clocks on the liver, for example, which regulate glucose metabolism.

Yeah. And if you, you know, don’t eat within a window where you’re most insulin-sensitive and you start eating later, then you’re going to have more inflammation because your blood glucose levels are going to rise and it’s going to cause all sorts of problems. Same thing goes with, you know, fatty acid metabolism, right? Yeah. And the intake of fat itself actually can inhibit the beta oxidation process. Yeah, yeah.

Right? So, you know, if you’re eating within this certain window, you’re affecting your metabolism. And that, in turn, would then affect inflammation. Yeah. Possibly. Yeah. So there’s also this idea that there is some amount of gut leakiness. And so some of the bacterial proteins or bacterial membrane component, for example LPS and a few other things, can leak through our gut lining into circulation. And that can illicit immune response. But we know that with time-restricted eating, since our gut repairs itself at night for us, then during fasting time the gut has enough time to repair so that the gut leakiness goes down. So in that way our immune system is actually less exposed to these antizymes that might leak through the gut. Right. That’s another way that inflammation can go down.

I remember a colleague of mine who his name is Mark Shigenaga. He was a former colleague of mine when I was doing a postdoc with Bruce Ames, he’s a brilliant guy, gut expert. And he was telling me all about… I remember him telling me about how the gut can handle a high fat meal the best in early in the morning. Yeah. Because of all these repair mechanisms and things that are happening. Like, the first thing in the morning, like, it’s better to eat…he was saying your high fat meal was more…your gut could handle it better than it could, like, later on in the evening. So it’s kind of interesting. But the LPS leakage and all this, very relevant for inflammation. Yeah. And the gut is one of the major sources of inflammation. Yeah. So the gut, the gut is also, you know, on a circadian rhythm.

And not just the microbiome, but, like, the, you know, the goblet cells in the gut and the ones that are making the gut barrier. And all these, you know, all these cells are on a circadian rhythm. Yeah. So it really does make sense that you want to eat within a certain time window for the health of your gut. Yeah. Right? One’s health starts from the gut. It’s our interaction, when we say health is a product of our nature versus nurture, our environment, one of the biggest interactions with our environment happens in the gut through our food and how the food is digested, how the microbiome handles that food, our digestion then sends it to our system. So that’s actually the interface between nature and nurture, so what happens there has huge impact. And we’re actually finding that the entire gut lining from esophagus all the way to cecum is strongly circadian.

There are many transporters, there are many bumps. And even the channels that absorb drugs and get into our liver, many of them are strongly circadian. And over the last two years there are also many papers that are coming out showing gut microbiome composition itself is circadian. So that means the bug in our system when we go to bed are very different from…we wake up with a different set of bugs in the morning. Right. And this diversity is much more important because a different set of bugs have their own specialization. So they break down or process different kinds of food, or they also offer different kinds of benefits. So in mouse experiments what we have seen is when mice eat a standard diet, a healthy diet, and they eat on a regular rhythm, so they eat mostly during nighttime because they’re nocturnal, and eat less during daytime, the their gut…the microbiome composition changes nicely in a rhythmic fashion throughout the day. But when they eat this high carb diet continuously, then that diversity goes down, their gut is mostly populated by a few meso microbes.

And then when they eat on a TRF fashion, when they eat only for 9 to10 hours, then some of the minor species that are almost obliterated on that constant eating, they slowly come back and they start to work. So we see that diversity component slowly coming back. Without even changing the composition. Without changing the composition, so the diversity comes up. Wow. Amazing. Yeah. That’s amazing. Do you know if shift workers have a higher incidence of, like, IBS or gut issues? I mean there’s certainly a higher incidence of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Yeah, so the shift workers always complain about gut disease. So gastrointestinal problem is the first thing they always report/complain about. So it makes sense from our mouse study and also from what we know from shift workers, that circadian rhythm or circadian eating pattern will have a huge impact there.

Yeah, so it makes sense. And what we know from how the gut microbiome also affects the way we’re absorbing nutrients, it would affect obesity, as well, right? Yeah. So that’s been shown. So maybe there’s also a link to that. So I think on a daily basis, like for example on a daily basis what would healthy, another definition of healthiness while going to be bed at night is not to have this acid reflux or heartburn.

Which is essentially a gut sodium…sorry, the proton pump working differently. And what we find in mouse studies is this expression of the level of this proton pump goes down on the time-restricted eating. So this is one example where many of our myCircadianClock users reported saying, “Oh, well, you know, the first benefit we found is our acid reflux has gone down, we don’t get that much heartburn.” And then we got curious, we went back to what are the targets of all the acid reflux drugs, and we found this proton pump. And interestingly this proton pump expression goes down in mouse gut. That’s awesome. That is so awesome. So this is another example where we would never ask about…we don’t have even the means to ask what is acid reflux and heartburn in a mouse, but we have a means to actually get this response from users and go back and ask the mechanism in a mouse. Yeah, it’s great. I’ve never…the first time I experienced acid reflux was during my pregnancy, late pregnancy, when my husband and I went out and had some, like, fancy meal. And I usually don’t ever, like, eat sugar or dessert, but I had, like, a little thing of, like, ice cream with some, like, chocolate or something.

And we were in a hotel, and then, like, we went to bed not long after. And I could believe how unbelievably painful and uncomfortable it was because I’ve never had it in my life. Apparently when you’re pregnant, it’s a problem because, you know, your stomach is getting… Yeah, squished. …squished. But, anyways, I decided at that moment I’m like, “I’m not eating out like that again,” because I don’t want to experience it. But just I’ve heard about so many people talking about acid reflux before and I never really knew.

I was like, “Oh,” you know, “So what? What is it?,” like, “Your stomach is upset.” Yeah. No, you can’t sleep. Yeah. It’s, like, burning. Yeah. It’s like something is coming out burning. It was awful, I had to, like… I could sleep, I had to sit up for, like, a couple of hours. So that, you know…the fact that TRE seems to be affecting, you know, acid reflux, you know, through this specific proton pump inhibitor in some people using your app is, like, super cool.

Yeah. The shift work is…so back to, like, the shift work and stuff. Because a lot of people have reached out and asked that are… I mean I think it’s something like 20% of the U. S.are shift workers, is that right? So in the U.S. 20% of the workforce is shift workers, but at the same time there are many who are…who may be shift workers, but they are not counted in the Department of Labor Statistics. Like who? So, for example… And nowadays you can include the taxi drivers or Uber drivers or Lyft drivers because they don’t classify themselves as shift workers.

They might have a one regular job that they list, but then in the evening and weekends or early morning they are kind of doing the second gig and they don’t list themselves. Then another thing that we came up with is what we call secondhand shift workers. So these are the family members of shift workers who have a lifestyle that are very similar to shift work.

And this is something that we found in a study, in the same myCircadianClock study, in India where we found some people who self-describe them as not shift worker, but then their eating pattern was like shift workers. So when we asked them again, then we realized that their spouses were shift workers. And to maintain that strong family bond they wanted to share meals with their shift work spouse, shift worker spouse. So in that way we call them the secondhand shift worker who are not working in shifts, but they are actually sleeping and eating like shift workers and they may be experiencing the same adverse metabolic consequences of shift work. Right.

So in that way the actual number of people, fraction of population, who are experiencing shift work-like phenomena for a few months or years in their lives may be upward of 30% or 40%. Wow. That’s a lot of people. That’s a lot of people. Because in India and China, the card-carrying shift workers in the workforce can be around 27% to 30%. And then a fraction of them have family members who are like shift workers because they’re secondhand shift workers. So it can be upward of 30%.

And some of the negative consequences that are pretty, I would say, scientific consequences that’s associated with shift work, what would be, like, the top few that you would say? Yeah. So cardiovascular disease is right on the top. And then obesity, diabetes. And actually the very early study on shift work and metabolic disease was linking shift work with diabetes and obesity. And then slowly we started to see that in many of the longitudinal studies with nurses or with health professionals, just random eating patterns and shift work increases cardiovascular disease risk. And then recently I came across this very interesting piece of data that I was not aware of that the number one cause of death and disability among firefighters in the U.S. is not actually related to fire, it’s cardiovascular disease and stroke. So that’s the number one cause, not even firefighting fire. So that tells us that all these chronic diseases are linked to shift work. And then there also is mounting evidence all over the world that shift work is tightly linked or increases the risk of certain kinds of cancers, including breast cancer.

So that’s why World Health Organization has categorized shift work as a potential carcinogen. So that’s a very serious classification because if we know that we have to stay away from carcinogens, even in buildings, if there is a carcinogen, there’s a potential carcinogen used as a paint or there is a reason, then we have to put a sticker. And to think about shift workers, they are actually doing something that’s a potential carcinogen. They do it almost on a daily basis for many, many years. So that’s why I think now there is increasing awareness how to manage shift work so that they will stay healthy and will reduce the risk of disease.

And they’re doing something beneficial. I mean firefighters, nurses, you know, police. I mean they’re helping society, so it’s not like you can just eliminate shift work, right? I mean you need shift work. No, actually our modern society is actually based on those heroes. So we actually call them the guardians of our society because they are the ones in the middle of the night, they are making the economy running, they are the ones who are hauling trucks, long distance trucks, and they are the ones who are actually transporting cargoes of a plane or ships. They are the ones in the middle of the night that are taking care of our health and to any emergency. So we have to kind of make sure that these heroes are healthy. So we have to kind of start thinking how to come up with a healthy heroes program where we can clearly say these are the lifestyles that they can adopt in relation to their being productive at work so that they stay healthy.

And one complexity with shift work is shift work is just not one type of shift, it’s a mixture of many different types of shifts. And, for example, firefighters may be on shift for 24 hours straight, whereas a nurse is on shift for only 12 hours. Some of the fast responders may be on shift only for eight hours. And then for them, for some of them, the shift might change two or three times within a month, so they may be on a day shift versus night shift, even within the same week.

Whereas in some departments and in some professions they can be on the same shift for three to four months, which helps them to adapt to that shift. So in that way I think it will be interesting to bring up this heterogeneity in shift work and figure out which kind of shift work is more manageable than others and perhaps figure out how we can help, firefighter kind of shift work versus nurse kind of shift work and first responders. Yeah. Do we know from any animal evidence… For example if you take an animal that is, you know, for example, nocturnal, like a rodent, a mouse, which usually eats at night, you force it to now not eat at night but to be awake during the day and eat at day and not eat at night.

So if you can shift them to not eat all day, all night, but eat just within a time-restricted eating window, do we know if they eventually adjust, how long it takes for them to adjust? Does their metabolism adjust? Does their circadian rhythm adjust? Yeah, so those studies have been done and there are many different ways to look at it. One is if we just give the same unhealthy high fat, high sucrose diet, instead of giving them at nighttime for 10 hours, for example, give them during daytime when they’re not supposed to eat, when they’re supposed to sleep. So the bottom line is if mice eat randomly, then any kind of time-restricted eating is better than that random eating. So even if they eat during daytime for 10 hours, that still gives them some benefits. So it’s still beneficial. So there are some concerns with animal experiments. One is if we feed animals during daytime, definitely they lose some sleep and they just eat. Unlike shift workers, they’re actually not working throughout the daytime, unless we force them to really work. So then it becomes a two-factor intervention.

And then at nighttime when they actually go back to their normal activity, they run around in the cage. So in that way they get a sleep deprivation pattern factor into it. So they are not as healthy as night-fed mice, but at the same time they have a strong sleep deprivation factor. So that’s why I think among shift workers, coming back to shift workers, if we can control for how much they sleep during their off time and they can sleep enough, if they come up with some sleep hygiene and adopt some sleep rituals that help them, and then they adopt the eating pattern that best suits their shift, then it might help. But eating still within a small, more narrow window. Yeah, still eating within a narrow window.

Then there is another piece of evidence that daytime eating of healthy food is still beneficial. And that comes from the area of caloric-restriction studies in rodents. So historically many caloric… CR studies in rodents are actually done in a way where the CR mice got their food during daytime. And in most the animal technicians come around in the morning, and then they see our mice get their food around 7:00 or 8:00 in the morning, and sometimes even after 9:00 or 10:00 in the morning.

And the caloric-restricted mice actually eat all of their food within two to three hours. So they eat. The CR mice So they wake and just eat because they’re hungry? Because that’s when they have food, access to food, because the animal techs actually give them food. And so they don’t sleep throughout the day and in the evening they eat, they actually eat right away. So we know from CR studies that all CR animals, most of the CR studies in rodents show tremendous health benefits, even though they eat the food during daytime.

Wow, I didn’t realize that was done that way. Yeah. So maybe another layer of complication could be not only just time-restricted eating, but eating less, as well? Well, so one caveat is in the CR study the ad libitum fed mice were fed ad libitum, so that means they were eating at nighttime. Oh. So they were never controlled to eat during the daytime. Oh. So I think those are the new type of studies that need to be done. But at least we know that if the animals, we reduce calories and fed them during daytime when they’re supposed to sleep, it doesn’t have any adverse impact, it actually gives them a lot of benefit. Now the question is if we give them the same number of calories as ad libitum fed mice during daytime, what happens? And we have done that experiment not with a standard diet, with a high fat diet. And with a high fat diet they are better than ad libitum fed. Right, right. So, okay. So I think for shift workers, if they can constrain to a certain number of hours, that’s better. They can improve nutrition, that’s still better.

They can reduce calories, then that will be, again, better. And if they couldn’t sleep, maybe do things to help them sleep better during the day. Yeah, during their off time. You know, dark, quiet, cool, all the things that help you sleep. Yeah. So there is sort of some hope possibly, possibly for shift workers. And maybe, you know, as more data comes out through your study with myCircadianClock and also as you get data from myCircadianClock app and then go to animals and look more mechanistically, things may come out even more. Another sort of question that sort of relates to this is, and people ask this all the time, is what about people that are…start eating later in the day? For example they wake up 8:00 in the morning, but they don’t eat until noon.

So let’s say they eat their first bite of food at noon, and they stop eating at 8:00 p.m. So that’s an 8:00 TRE eating window. And they go to bed by 11:00 or so. Do they still have the same benefits or are they losing because it’s like the time-restricted eating window has kind of shifted to later and obviously there is a light/darkness component to all this to some degree? Yeah, yeah.

So those questions we haven’t even teased them in animal models, but I’m sure some people will start teasing them apart. So what happens is in the morning we know insulin sensitivity is at its best. So people who have a bigger meal earlier in the day, they have less insulin spike, less glucose spike, etc. Having said that, we don’t know for people who are starting their food every day at noon whether they’re best insulin sensitivity is at noon or it actually happens at 8:00 in the morning. So that information we don’t know. So this is where some studies need human volunteers who are doing this.

And maybe some people who are doing…who are starting to eat at noon, one day maybe they can drink a glass of juice at 8:00 and prick themselves and get a glucose reading and monitor themselves. And then another day, a week later at noon, they will eat the same glass of juice and prick themselves and see how is their glucose response. So that’s a simple self-experimentation with some healthy people. If they’re out there, then they can do that. And if they post it, that will be really nice. Second thing is what happens toward the end of the day at night. So this is where it becomes a little bit complicated because, as you said, there is day and night transition. And we know that in the evening as our body prepares to sleep, our melatonin level begins to rise. And that melatonin usually rises two to three hours before our habitual sleep time. So if somebody is going to bed around 11:00, then that melatonin is beginning to rise around 9:00.

On an average, but some people it might rise around four hours early and some people it will rise exactly at bedtime. And when melatonin rises, there is new data showing that melatonin can bind to its receptor in the pancreas. And this engagement of melatonin with the pancreas receptor essentially tells the pancreas, “Okay, it’s time to sleep, you don’t have to bother releasing insulin.” So in that way what happens if somebody is having a big meal when there’s high melatonin, then there may not be enough insulin to release from the pancreas and glucose may stay high in the blood circulation for a long time. And this study…these kind of studies came to publication because almost 10 years ago large genome-wide association studies found that people with obesity or diabetes might have a mutation in melatonin receptor. And that was confusing because what has melatonin to do with obesity and diabetes? And you fast-forward 10 years, people went back to the drawing board and looked at where the receptor is expressed and what it does when melatonin is engaged, and then they found out that there is this effect of melatonin on insulin.

So that’s why people who are eating late into the night, they may not get the best benefit in terms of glucose control because their glucose might remain slightly higher than if they had the same dinner two hours earlier. If they’re making more melatonin. If they’re making melatonin. So it’s very…so that’s why I said it’s complicated. Yeah. But at the same time I would say eating randomly over 12 hours, 15 hours, versus eating to this 8 hours, even though it starts at noon, I will prefer the 8 hours starting at noon. Right. So it seems like there’s, in addition to, you know, the timing of your food intake, so we know the first time you’re eating sort of starts a lot of these liver enzymes and metabolism…glucose metabolism and all these things. In addition to that, that circadian rhythm being regulated by just the food intake, there’s also this whole melatonin issue and the night-daylight cycle and, you know, when you’re starting to make more melatonin.

And all that complicates things, as well. Yeah. It seems. Yeah, I remember a study that was done where I think men were given the same caloric meal in the morning and the evening. Yeah. And glucose was measured and the blood glucose levels were much higher in the evening versus morning. But, of course, they could have been. Who knows how long… You know, was the morning, like, 8:00 a.m. , and then they were doing, you know, 9:00 p.m.or 8:00? So who knows what their timing window was, right? The habitual meal, what is their habitual meal? Right.

That’s a very widely observed phenomenon. In fact, there was a term for that that was called evening diabetes. So a person might be healthy in the morning based on blood glucose. In the evening if you do the same postprandial glucose tolerance test and then look at the glucose level, then maybe diagnosed diabetic. Right, right, yeah. Yeah. Well, I think the other component to this would be the fasting component, right? So people think, “Well, I’m only eating within an eight-hour window, so I have a much longer fasting period.” And I think that’s maybe uncoupling some of these differences between time-restricted eating, being on a circadian rhythm, and fasting, intermittent fasting, prolonged fasting. You know, there’s so many different terms out there. Yeah. And I think sometimes a lot of it just all gets mushed together in one group and it’s, like, all the same. Yeah. But it’s not actually all the same. No, it’s not the same. So, for example, even not having food in your system for 12 to 16 hours, whether it’s fasting or not, that’s debatable.

Because some people say, “Well, it’s not fasting, it’s not having food for 12 hours.” And I think that’s where I would say not having food for 12 to 16 hours is not fasting, but maybe giving rest to your system, rest and repair and rejuvenation of your system. So when we think about fasting, or when you think about fasting, two things come to mind. Feeling hungry. And feeling hungry has many different connotations, many different intensity. So one sense of feeling hungry is, well, you might feel light. And then second, your stomach may begin to frump a little bit. And then I always say that is your stomach is telling you, “Well, I’m repairing myself.” You’re not actually really hungry, you’re not getting low energy that you cannot get up from the chair or run or something like that.

And then after several, maybe one or two, days of fasting, or maybe after 24 hours of fasting, some people will get a head ache. So that’s a good sign that, well, your brain is not getting enough energy in its habitual usual form and may be trying to signal the rest of the body that the body has to send some other form of energy, for example ketone bodies or something. So in that way fasting, if you’re measuring fasting or you’re defining fasting in terms of ketone body formation above a certain level, then that may kick in after 24 hours. Or if you have that threshold even much higher than fasting, maybe 20, 48, or 72, or even 96 hours before you see that level of ketone bodies that can be your definition of fasting. So in that way I think the way you define fasting will determine whether 24 hours, 48 hours, 96 hours, or even 12 hours or 16 hours is fasting. But the way we think, we kind of define how many hours your system should not have food is based on our daily circadian rhythm. Because if you think about what are the key elements to being healthy, it boils down to three important things.

One is sleep, and the second one is nutritional food, and the third one is physical activity. And these three are interlinked with each other. So, for example, if somebody is sleep deprived or didn’t have sleep, then it’s very hard for that person to do physical activity the next day or go on a marathon. So these two are interlinked. Similarly, if somebody is eating for 15, 16 hours and has a very heavy meal at the end of the day, then it affects sleep. It also affects physical activity. One cannot run with a full stomach. So these three are interrelated. So on a daily basis what we feel is having…limiting food to 8 to 10, or maximum 12, hours helps to coordinate these three foundations of health to work on a daily basis and give us healthy benefit.

So on a very simple sense if I want to relate time-restricted eating and then maybe long-term fasting, one day of fasting, two days of fasting, or four days of fasting, which definitely have much more benefit, then it’s almost like taking care of your teeth. So brushing every day is like time-restricted eating. There’s the minimum one can do and that’s something necessary to take care of your teeth. But, again, once in a while, maybe twice a year or three times a year or once a year, depending on how much you want to take care of your teeth, you want to go see a dentist.

So that’s almost like a prolonged fast one has to do once a year. So similarly I do four to five days of water fasting only once a year and that absolves all the other sins with my feeding that I might have committed throughout the year. So in that way I think the difference between time-restricted eating and other forms of fasting is one can adopt time-restricted eating as a true lifestyle, starting even from teenage or even toddler years, all the way through when you are 80s, 90s, or even 100 years old. Whereas this long-term fasting, two days or four days of fasting, forget about even teenagers doing it.

And some older people who are very fragile, they might not be able to do it. And you need medical intervention or some kind of supervision to do it. Many people who are slightly unhealthy, even some diabetics who might go hypoglycemic after 10, 12 hours, type II diabetic I mean, they may not be able to do it without medical supervision. So although those long-term fasting definitely have much benefit, and that has been shown in multiple studies, the need is that they can be practiced only by a certain type of people at certain days and need more mental resolve. And it may not be an everyday lifestyle, whereas time-restricted eating can be an everyday lifestyle. That’s a great way of putting it. It sounds like also you’re saying, depending on what you’re looking at, what biomarker you’re looking at downstream, that also can sort of define something differently.

For example, if you’re looking at autophagy or apoptosis that’s happening, you may not see or be able to even measure it. Maybe it’s happening, but you can’t really measure it well until you’re getting a more prolonged fast, like when you don’t eat for four days. Yeah. Whereas, you know, obviously when you’re not eating for 16 hours, if you’re doing a time-restricted eating schedule of eating within eight hours and you’re fasting every night for 16 hours, you’re in a fasted state in a way.

I mean maybe it’s not fasting, but, you know, you’re liver glycogen starts to deplete at, like, 10 hours of not eating and, you know, something like this. And your, you know, adipose tissue is releasing fatty acids and, you know, you do start making some ketone bodies. You wouldn’t necessarily be in a high level of ketosis or anything, but, you know, protein deacetylation starts to go down and, you know, these NAD levels rise. Yeah. So it’s like depending on what you’re looking at, I mean these things do start to happen, like in between meals even. Yeah. So to some degree you can be in a fasted state, maybe, and not be necessarily fasting. I mean it depends on where you set the threshold and whether people can reliably measure that, say, ketone body or even autophagy level when beyond that threshold.

So what used to happen was most labs, the vast majority of labs, they’re not circadian labs. And many of the postdocs and grad students and kind of really the ground soldiers who are driving science, they might have different schedules. So what happens, they come to the lab at different times, and then they might be doing the assay at different times without any control of when the animals were fed or how long they were fed or what type of food they had access to. And then even if the mice had 12 hours of fasting or 16 hours of fasting, one might get a result which is slightly higher than what it was without fasting with food. But it’s no reproducible because, as we know in circadian rhythm, the same parameter can change over time. Even if we measure just fasting insulin level in mice, for example, or fasting glucose level, that has a very slow, very small change. So in many cases people might discount it as noise in their system because somebody did the experiment in the morning, someone did it in the evening, their bellies are different, so they’ll say, “This is noise.” So that’s why people have come up with the longer fasting to see the threshold to set a higher threshold that they can reproducibly say, “This is signal,” irrespective of what time of the day the postdoc or grad student did the experiment. Right.

But then in the circadian lab what we do, we systematically…we are very careful about timing. So we will sample every one hour, to hours, three hours the same animal over multiple days, one day, two days, or even sometimes three days. And then we ask a very simple question, “Does it rise reproducibly every day around the same time?” Suppose, say, the ketone bodies do rise. And they may not go from 0 to 100, but they go from 0 to 10, every day they go from 0 to 10. Then the second question is, “What is the benefit of ketone bodies going to 10 from 0 on brain function or muscle function or heart function?” It’s possible that maybe your brain may not get much benefit, but muscle and heart are getting some benefit.

And in that way you can see that if we carefully monitor and then ask specifically what are the benefits, you can come up with ways where we can say even this 12 hours of fasting, or not having the food in your system, will create some amount of benefit for heart on a daily basis or some amount of benefit for muscle on a daily basis. So that’s why it becomes very difficult, what is fasting, what is autophagy, can we trigger autophagy only by 12 hours fasting or 16 hours fasting, versus 4 days of fasting. Because autophagy may go from 0 to 10, it might benefit only one or two organ systems, it might benefit 10 organ systems. Does it go from 0 to 10? Like, for example, when… Yeah, so autophagy, we have actually published papers showing that autophagy flux and autophagy gene expression does cycle on a daily basis.

And it’s directly regulated by some of the clock components. So mice, genetically and mutant mice, that don’t have these clock components, autophagy level is set high, or the autophagy level is set low, depending on which component will turn up. Does it go up during the fasted and/rested period? Yes. It does go up during a fasting phase in liver.

In liver? Yeah. That’s really cool. So the… I kind of got sidetracked here with this autophagy because I’m very interested in it. Because it’s a part of the repair process. Yeah. And the thing that’s so interesting is this repair process being, you know, in the fasting state and, you know, happening during the fasting state. And, like you said, maybe there’s a threshold where, you know, it’s like obviously if you’re fasting for 14 or 16 hours every single day because you’re eating within a time-restricted eating window, that’s also going to have benefits. And now the threshold may be…you know, you may have less of those benefits, but you’re not cleaning up. You know, you don’t have widespread apoptosis happening where you’re killing off all the damaged cells, but you may be clearing up some protein aggregates or something, you know, every day sort of on this steady state sort of level, which also is extremely important.

Yeah, it’s almost like, you know, if you have a carpet, if you vacuum it every day or every other day, then that remains clean. But at the same time maybe once a year you need a deep clean, a wet vacuum. Right. But if you don’t do that daily vacuum, or at least once in two days or three days, then that gunk will accumulate. It’s going to accumulate and it’s going to cause damage. Yeah. So that’s why this daily cleaning, even though it’s a low level, very low level cleaning of the system, that has a huge impact, that goes a long way. Have you guys ever looked at, like, DNA damage or repairing any sort of challenge? Like if you irradiate…

Like animals that are eaten, you know, on a time-restricted, you know, feeding sort of schedule where they’re eating their food, being fed their food, you know, within 10 hours or so, and then challenge them. With radiation or something? Can they, like, repair the damage better because they’re fasting longer? Yeah. So the circadian clock itself has a huge impact on DNA damage repair and radiation damage repair. So a few years ago we had done a simple experiment that got highlighted in National Cancer Institute website. There’s a very simple, straightforward experiment. We always asked…we asked a very simple question, that is, “How come humans’ skin is always exposed to sunlight or UV radiation and many people get skin cancer but they never get hair cancer?” Because a hair follicle has the most rapidly dividing cells.

And so one would expect that they must be most sensitive to radiation damage. And if there is any radiation damage, that’s where the tumors will start. And we rarely see that. So we went back and checked and we realized that the hair follicles at the base of the hair actually have a very strong circadian rhythm. And every evening that circadian clock repairs all the damaged DNA and makes sure that the hair can grow back the next day, next morning.

And then we asked, “So what is the real significance in real life?” So we took these mice and then did a simple experiment. That is, you know, for many bone marrow transplant experiments, mice are irradiated, and then their bone marrow is depleted and one can put the new bone marrow in. And they get irradiated to the same extent as humans do. They don’t die, they actually survive pretty well. And if we irradiate mice in the morning, 8:00, then those mice lose 85% of their hair. And if we irradiate the same mice with the same dose at 8:00 in the evening they retain 85% of their hair. So it’s a big, like really, black and white difference because these morning irradiated mice essentially become bald very quickly.

And the evening irradiated mice, they keep their hair perfectly fine. Now if we take circadian clock mutant mice where the circadian clock is absent, irrespective of what time we irradiate the mice, they always lost hair. Of course the story was much more about what…which DNA repair enzymes are regulated by clock and how this clock works, but this is a very simple, straightforward experiment. And similarly people have also shown many patients do go through partial hepatectomy. Or people who have liver cancer, part of the liver is resected, and then the liver grows back. And, in mouse experiments at least, if partial hepatectomy is done in the evening, then those mice recover much faster than those where the hepatectomy was done in the daytime. So that has inspired some people to think about this surgery time, what time surgery should be done and/or radiation should be done. So these are some just new ideas that have just come up in animal models in the last five to 10 years, so it will take some time to really get some traction in human studies.

Yeah. It will be interesting to figure out whether it’s, you know, the combination of is it because they’re, you know, getting more rest during that time, during the evening, and then they’re resting, fasted and resting, and so, you know, the combination of them all. Yeah. So we know that the tumors grow slower in mice that eat only within certain times.

So time-restricted fed mice, if we just implant a tumor, then the tumor will not grow as much as the mice that eat randomly the same number of calories. Wow. And that also jives with another piece of data that came from Ruth Patterson’s group that women who fast for 13 hours overnight are protected from breast cancer. They have, like, a 36% lower breast cancer occurrence. Yeah, yeah. Yeah. So that’s really cool. I wonder if with at least the animal experiments where you’re implanting the tumor and they’re fed at a time-restricted feeding schedule, then if they’re having more apoptosis, more autophagy, more DNA repair, all these things are all sort of simultaneously happening because they’re in a fasted state for longer? Yeah. Possibly? So it’s possible. Yeah. Yeah. Very cool and interesting. The other thing that is sort of on this whole fasting versus TRE topic that gets asked a lot that I have to ask you has to do with coffee. Actually, specifically caffeine, like black coffee. So without any cream or any calories or anything like that. So caffeine can start things, like the clocks in your liver? Yeah, it resets the clock. Because the clock is always running, it just resets.

It resets it, okay. So a lot of people in the intermittent fasting community, they do a lot of fasting, whether, you know, they’re fasting for 16, 24 hours, 48 hours, but they drink caffeine and they notice that they lose weight. And so they say, “Well, I’m still getting results.” Yeah. You know, “So it’s fine, I can drink my black coffee.” Yeah. You know, obviously someone that’s fasting for 48 hours, it’s very different than doing the TRE schedule where you’re eating for 10 hours a day or 11 hours a day, and then fasting for, you know, 13 or 14 hours every night, right? Yeah. So if a person, for example, that wakes up in the morning drinks black coffee at 7:00 a.m. They wake up, have some black coffee at 7:00 a.m. But they don’t eat anything, they don’t eat their first bite of food until… 10:00 or 11:00. Yeah. Yeah, something. Then when do they have to stop eating by? Like, is it when the coffee started or is it when they ate the food? Yeah, so this is a question we also get through the app a lot.

And we actually posted a blog on our website. So here is a very different thing. So since we look at circadian rhythm as a whole, it has a sleep component, food component, exercise or activity component. And we know that caffeine resets the body clock. So, for example, drinking a cup of coffee is similar to having exposure to bright light for an hour or hour and a half. So that’s just on the circadian clock itself. Now the question is, “Well, will it reset that clock the same way if the coffee comes in the morning versus evening or night?” And we know that there is a term called phase response curve.

So that means the same light, it relates to light. The same light will reset the clock differently at different times of the day. During daytime when your system is expecting light, if you’re in a dark room and we see light it doesn’t reset our clock. But in nighttime it will reset our clock. So we don’t know what is the phase response curve for coffee, whether it resets much more at certain times and less at other times. The direct impact of coffee on clock is unknown. Then the second thing that relates to coffee is sleep because coffee definitely suppresses sleep in a lot of people, some people may be resistant. And the reason why we drink coffee is we wake up, we get up from the bed, but we maybe are still feeling sleepy. We want to get that extra energy, that’s why we drink coffee. And along that line, of course, drinking coffee at night is a straight no-no because it will have impact on sleep. But in the morning we ask the other question, “Are you drinking coffee because you did not rest well, you did not rest enough?” So maybe that’s why you need coffee to reset your mental clock, or brain clock, to start it.

And sometimes it can be just a pure habit or addiction. For example, I used to like coffee in the morning, and then I realized, “Well, let’s get rid of coffee. What happens?” Maybe for the first two or three days I got a headache, and then now I’m used to drinking just hot water. It’s just the feeling of sipping something from a sippy cup. It’s almost like a baby sipping something from a sippy cup. And I realized that that’s what I was addicted to. I can actually substitute coffee with hot water and nothing changed. I still felt energetic after my hot water and I realized that that was my addiction. After you got over the…

After I got over the first two days of headache. …withdraw. Yeah, withdraw symptoms. And then it’s always the question of metabolism. When we drink coffee, is it going to trigger metabolism or certain things in our gut so that the gut will think, “Well, now I have to start working, the rest is over”? And we think that’s where the metabolism or the function of the gut to absorb, or digest this coffee, send that caffeine to liver, and then to brain does kick start right after we drink coffee. Because that’s how we are feeling the effect of coffee in the rest our body, because the stomach started working, it absorbed coffee, it sent it to liver, liver might have metabolized it slightly and started to send it to the rest of the brain and body.

And then it gets back to kidney, it gets metabolized and excreted. So then the question is, forget about circadian clock, now if we think about just metabolism and, say, mitochondria function, or even, say, go back to autophagy, and then ask, “Is caffeine breaking the fasting so that it stops autophagy, or it stops something else? Or is there a crosstalk between, say, caffeine receptor and glucagon receptor so that it does?” No, fasting is kind of slightly over. You may not be in 100% fast, but in 40% or 50% fast. So that’s where things become murky, so that’s why we say, “Well, if you can, drink your coffee within this 8-hour, 10-hour, it’s better.” But at the same time we know, going back to the study that we discussed, Ruth Patterson study, they did not consider coffee as food.

So when they considered 13 hours overnight fasting, that 13 hours actually included coffee and tea. So in that we know for cancer, reducing breast cancer risk, this 13 hours of fasting can include coffee, black coffee, and tea. So this is where things are really murky. And we tend to error on the safe side, so we tell, well, if you can have that coffee within your eating window, that’s much better. If you can’t, then just have black coffee.

At least that will not trigger your insulin response or glucose response. So that’s what we do, we recommend. Just sort of as a side note because you mentioned it, I recently spoke with Dr. Guido Kroemer, who is an expert on autophagy, and he was telling me about a study he had published a few years ago where the specific polyphenols in coffee, decaf or caffeinated… So irrespective of caffeine, it’s just it’s the polyphenols. Yeah. They triggered protein deacetylation, which is one of the triggers for autophagy.

So it actually increased autophagy. Increased autophagy, yeah. So that’s why we never know, because coffee, or any natural compound, has so many different ingredients that we don’t know the activity. Yeah. And many of them can have very different effects. When we think of food, we have mostly…the nutrition science, or most of the scientists, are latched onto the effect of protein, carbohydrates, and fat.

We discount a lot of xenobiotic. And actually our food is, the majority of it is xenobiotic. Right. And we have no idea what do they do, either alone or in combination. Right. And that actually…that’s another question. I printed out some, but that is a question that’s frequently asked by people in the audience. Is, like, things that are xenobiotic, like herbal tea, even, I guess, to some degree people are asking about flavored water. So water that would contain, for example, like or stevia or something, you know, does that start the clock? And I think you’ve kind of answered that a little bit. Yeah. So in that way it may not stop the clock and, also, for your insulin response it’s not actually triggering the pancreas to secrete extra insulin.

You know, insulin is an anabolic hormone, so it’s not actually putting our body into a strong anabolic drive. So in that way, in many ways, it’s okay to have this non-calorie-containing food. But then it gets murkier once we go to, say, Diet Coke or something else where there is artificial sweetener, and then we know that the artificial sweeteners have an impact on gut microbiome. And that’s where things become murky. Right. And these are very practical questions, but at the same time we don’t foresee that even there will be any controlled clinical trial to assess the effect of these nutraceuticals or even things that we take for granted on a daily basis. So this is where, again, the N of one experiment, self-experimentation of yourself, trying different kinds of behavior intervention where you switch from water to flavored water and does it make you feel different. I mean it’s not only weight gain. One has to assess sleep, activity, feeling alert, feeling productive. Maybe measuring your fasting blood glucose levels. Blood glucose level if you have a continuous glucose monitoring system. Right, even better. And so this is where strongly this self-experimentation by informed citizens who are very careful, they’re not really…they don’t have any adverse metabolic disease.

And, again, I’m not promoting that everyone should start doing self-experimentation. People are doing it. But as least whatever they’re seeing they should share. Yeah, they could share it with myCircadianClock. Yeah. So even if they put some notes in the feedback section, then we’ll compile all of those, and then that will help us to take informed decision about animal experiments. At least we can go back to animals and say, “At least in animals we have tested this, this is how it works.” Right. And in the future maybe that will trigger some… Or maybe you’ll get 10 people to come back and say, “Oh, I started drinking my,” you know, “Diet Coke in my fasting window and all of a sudden my blood glucose level started to get worse.” Yeah.

So you’ll have multiple people telling you this. Well, maybe there’s something to that. Yeah, yeah. But, you know, people are asking about things, like even supplements. And I think, like, you know, again, you’ve answered that we don’t, you know… You know, are you taking fish oil? Is it a fatty acid? I mean maybe… There’s lots of things here because that is, you know… So if you’re taking a fish oil supplement, then what do you think? That’s different than taking, for example, vitamin D? Well, it’s a question of… I like to compare this to, say, physical activity.

Somebody is completely sedentary. For that person going for a walk, whether it’s in the morning or evening or midnight doesn’t matter because this person is getting some benefit of physical activity. Similarly, if somebody is very low on vitamin D or needs that fish oil supplement, then what time the person takes doesn’t matter because that deficiency is getting corrected. Yeah, that’s true. So that’s true. But then if someone now dials it slightly higher and says, “Well, you know, I want to have this protein drinks that’s 25 grams of protein after my exercise late at night. Is it okay?” Then that’s where I’ll say, “Well, then that’s going to affect your gluconeogenesis and muscle recovery.

And maybe if you have done a very strenuous exercise, if you’re training for, like, Ironman or something like that, yes, you have to have that to recovery. Yeah. So that was actually a question I think people were… Someone was asking about weight training at night, if that would counter. If they, you know, eat late at night after weight training, if that would counter. And I think that’s kind of pushing it a little bit. Yeah, that’s pushing a little bit. Which is kind of what you’re saying. And, again, it depends on your training schedule and other stuff, what do you want to get the most out of it. Like, for example, if you’re used to training late at night and having that protein and carb drink right after that, what if you do a little self-experimentation and move that to, say, 5:00 or 6:00 and see whether it actually helps you do one extra pushup or to go for another five minutes, or is it actually compromising your performance.

So, again, it’s very personal. And then some of these very kind of athletes who are pushing themselves to the limit, they want to squeeze the last drop of performance out of it. And for them I think self-experimentation is the best way because there is no way we as scientists, we can do that kind of study in our labs with a number of subjects who are as competent as them, and then controlling for everything. So it would be very difficult. But you did show in one of your animal studies that a shorter feeding window for these animals, like, for example, nine hours…or it was eight or nine hours. Eight to nine, both of them. Endurance… Endurance went up. …performance went up. So you do have some evidence of being able to squeeze the last drop of performance maybe.

Yeah. So that way you clearly see endurance went up. And the reason why we did that experiment was we thought, “Well, if the mice are feeling fasted for a long time, will their athletic performance or muscle performance go down?” Because our worry was their performance, athletic performance, might go down. And in that way it might be harmful for some people for whom physical activity is needed. And, for example, many shift workers, they need that physical performance. Right. That’s why we did it. And we realized that their grip strength, which is similar to how much weight a person can lift, that did not change, that stayed the same. But the endurance, being on the treadmill for a long time, that actually significantly increased, and in some cases it doubles. Doubles? Yeah. I’ve noticed this in myself. I’ve done, like, an eight or nine-hour eating, you know, schedule and the next day… So if I’m fasting for a longer period, the next day I go for a run in the morning and my endurance is… And this is, I mean, we’re talking like five or six times, maybe seven times I’ve noticed it. Yeah, yeah.

I mean it’s a clear pattern. Yeah. My endurance is dramatically improved. I mean it’s incredible, like, I just can keep running. Like, whereas usually I’m tired and I reach the mark where I’m like, “Okay, this is it, finally I’m getting”… You know, you kind of sprint to the end and now I just keep going. Yeah. No, we see that. There are many people who have given us this feedback that their endurance does go up. And then what is interesting is, again, their endurance improves, and then once in a while they say, “Well, I can go back to 12 hours,” and then immediately they see the reversal of that endurance. Right. It does, exactly. It totally reverses, yeah.

Yeah. You know, I know there’s been some recent studies coming out in the last year or so where exogenous ketone bodies have been given to endurance athletes and it improved their endurance capacity. Which makes sense because endurance heavily relies on mitochondria. Right? So, I mean, it completely… I mean if that’s actually part of the mechanism with the time-restricted eating in terms of a longer faster period one would presume would have higher levels of ketone bodies.

Yeah, we do see they have a slightly higher level of ketone bodies. So it makes sense. Yeah. Whereas… Well, I don’t know what exactly you’re doing with the grip strength, but, you know, it depends on whether or not if you’re pushing them to a high enough intensity where they’re becoming glycolytic or not. I don’t know. Yeah. So, again, we don’t know where the dynamic range of that particular assay and we can’t ask questions to mice. So this is where people who are actually lifting weights are doing something, a very different kind of exercise. Endurance exercise versus intense exercise, those are very different. Maybe they can give us feedback to see what happens. Now in your study wasn’t there improved lean muscle mass? Yes, we did see lean muscle mass improvement only on mice that were given standard diet, not on high fat diet.

Okay. The high fat diet fed mice… Yeah, I wouldn’t expect for them. So they were given…so the mice that were given the normal, sort of healthier diet. Yeah. What was their eating schedule? They were eight to nine hours. So it was a shorter time window they were eating? Yeah, yeah yeah. They had increased lean muscle mass. Now is that something, like, do you know why that is? Has that been looked at? We actually don’t understand that, that’s another thing. But we do see there is an increase in PGC-1 expression in muscle, so there might be an increase in mitochondria function. But surprisingly in the same mice we saw there is less glycogen in muscle. And that’s kind of counterintuitive. You might think that, “Well, the muscles may be loaded with glycogen, so that’s why their lean mass went up.” But at the same time what we think is maybe, because they have less glycogen, we know that if the muscle has less glycogen than after normal activity, then glycogen may be completely depleted.

And when they eat, they have a much better feeding response. So that means a much better glycogen synthesis response. So they may be making and breaking glycogen, making and breaking triglyceride on a daily basis, or protein on a daily basis. So in that way I think they may be maintaining much better muscle health. Because they’re also going through some gluconeogenesis, they’re breaking down some protein. So maybe some of the structural proteins that get modified and maybe they get damaged, they’re kind of getting cleansed, they’re getting cleaned out of the system by this eating and fasting rhythm. So, again, it’s all speculation, so we have to go back to the muscle samples. Yeah. You have the data, you just don’t know the mechanism. We don’t know the mechanism. But people are very interested. I mean increasing lean muscle mass is hard to do and there’s a lot of huge interest in it.