Domestic abuse comes in digital forms as well as physical and emotional, but a lack of tools to address this kind of behavior leaves many victims unprotected and desperate for help. This Cornell project aims to define and detect digital abuse in a systematic way.

Digital abuse may be many things: hacking the victim’s computer, using knowledge of passwords or personal date to impersonate them or interfere with their presence online, accessing photos to track their location and so on. As with other forms of abuse, there are as many patterns as there are people who suffer from it.

But with something like emotional abuse, there are decades of studies and clinical approaches to address how to categorize and cope with it. Not so with newer phenomena like being hacked or stalked via social media. That means there’s little standard playbook for them, and both abused and those helping them are left scrambling for answers.

“Prior to this work, people were reporting that the abusers were very sophisticated hackers, and clients were receiving inconsistent advice. Some people were saying, ‘Throw your device out.’ Other people were saying, ‘Delete the app.’ But there wasn’t a clear understanding of how this abuse was happening and why it was happening,” explained Diana Freed, a doctoral student at Cornell Tech and co-author of a new paper about digital abuse.

“They were making their best efforts, but there was no uniform way to address this,” said co-author Sam Havron. “They were using Google to try to help clients with their abuse situations.”

Investigating this problem with the help of a National Science Foundation grant to examine the role of tech in domestic abuse, they and some professor collaborators at Cornell and NYU came up with a new approach.

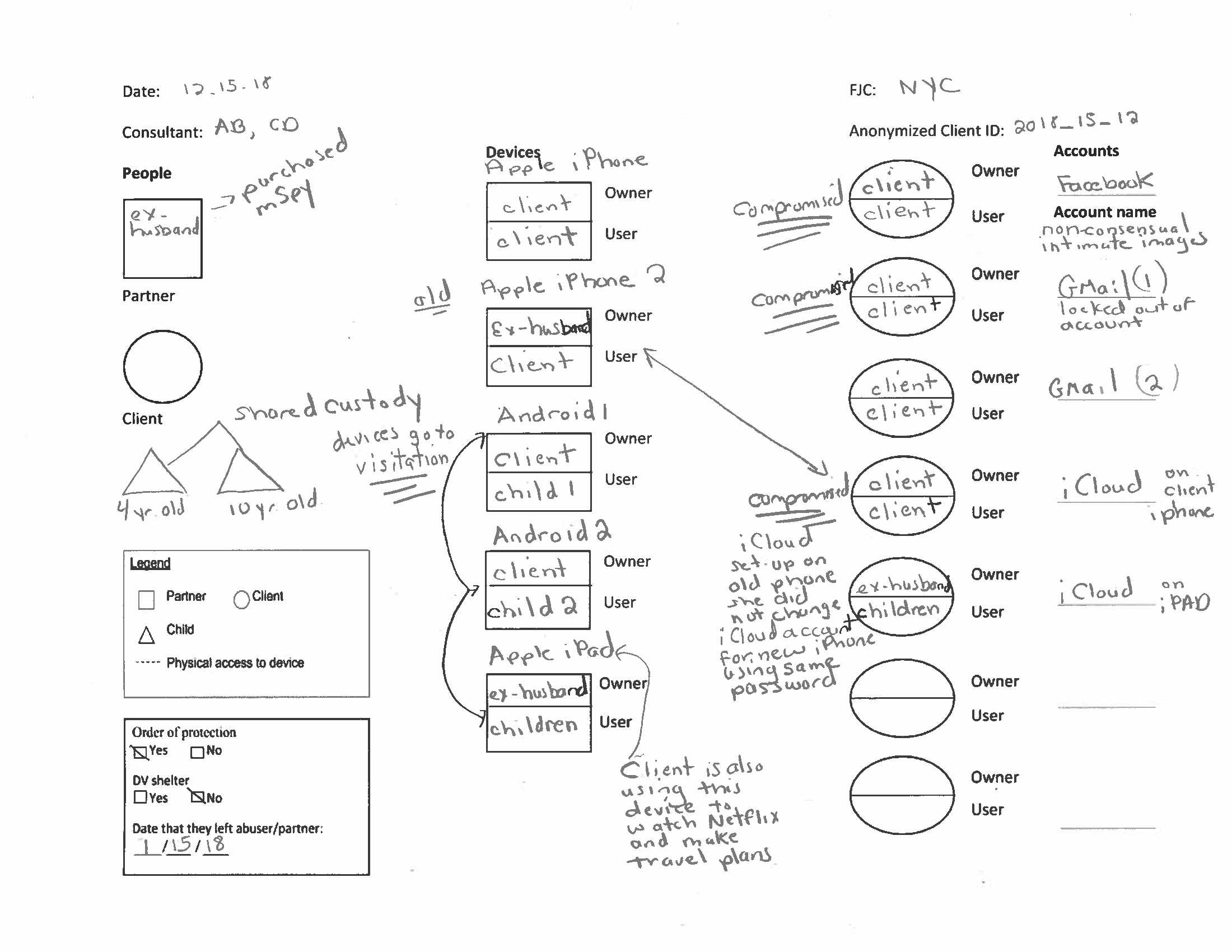

There’s a standardized questionnaire to characterize the type of tech-based abuse being experienced. It may not occur to someone who isn’t tech-savvy that their partner may know their passwords, or that there are social media settings they can use to prevent that partner from seeing their posts. This information and other data are added to a sort of digital presence diagram the team calls the “technograph” and which helps the victim visualize their technological assets and exposure.

The team also created a device they call the IPV Spyware Discovery, or ISDi. It’s basically spyware scanning software loaded on a device that can check the victim’s device without having to install anything. This is important because an abuser may have installed tracking software that would alert them if the victim is trying to remove it. Sound extreme? Not to people fighting a custody battle who can’t seem to escape the all-seeing eye of an abusive ex. And these spying tools are readily available for purchase.

“It’s consistent, it’s data-driven and it takes into account at each phase what the abuser will know if the client makes changes. This is giving people a more accurate way to make decisions and providing them with a comprehensive understanding of how things are happening,” explained Freed.

Even if the abuse can’t be instantly counteracted, it can be helpful simply to understand it and know that there are some steps that can be taken to help.

The authors have been piloting their work at New York’s Family Justice Centers, and following some testing have released the complete set of documents and tools for anyone to use.

This isn’t the team’s first piece of work on the topic — you can read their other papers and learn more about their ongoing research at the Intimate Partner Violence Tech Research program site.