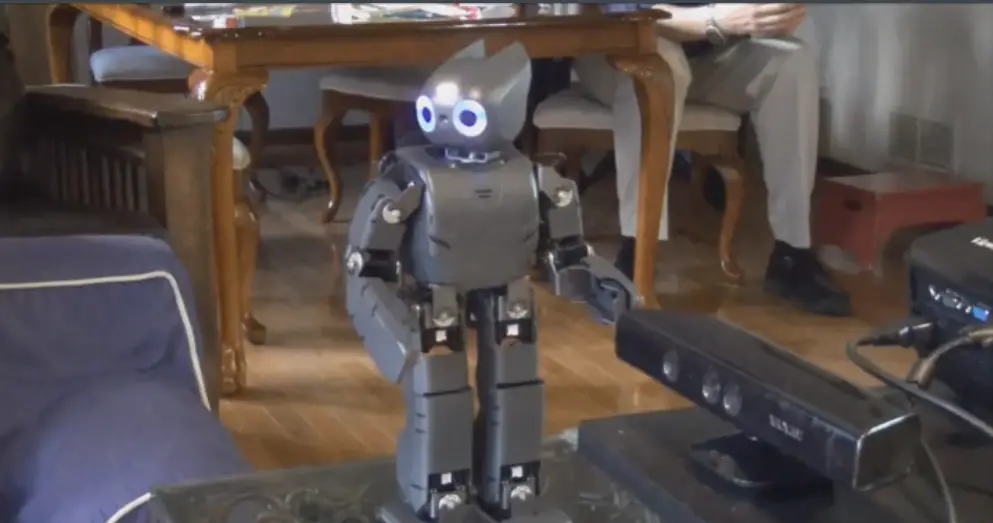

A young girl in Atlanta manages the symptoms of cerebral palsy with regular physical therapy, which normally means a visit to a doctor’s office, or hours of boring, repetitive actions on her own. Recently though, she began taking instructions, at home, from a pint-sized robot physical therapist called Darwin.

Researchers at Georgia Institute of Technology are using robots to help children and adults meet their physical therapy goals. And they’ve found that combining a simple game with words of encouragement and physical cues from the robots provides a noticeable boost to patients’ efforts, compared to asking them to go through the work on their own.

In the experiments, the researchers used a 3-D motion tracker to monitor a subject’s movements, with Darwin offering encouragement for the correct motions, or demonstrating if a person did them incorrectly. In all but one case, they found that using the robot helped increase physical activity significantly.

“One of the primary issues with therapy is that kids aren’t getting enough of it,” says Ayanna Howard, a professor at Georgia Tech who leads the project involving Darwin. “For it to be effective, you need to do it every day.”

As robotic hardware gets cheaper and easier to program, robots may start appearing in some surprising areas of everyday life. A robot might not replace a physical therapist, but it could help provide routine direction and encouragement that would normally be too expensive to offer to everyone. Indeed, a number of companies are now developing simple robotic assistants for the home (see “Meet Kuri, Another Friendly Robot for Your Home”).

Industrial robot arms could easily be combined with computer vision systems to provide simple home assistance. “If you look at some of the robot hardware that’s coming out, it can be repurposed; the power is in the algorithms,” Howard says.

Howard and her team are exploring ways that robots might help with routine child-care tasks. She suggests that robots could help in daycare settings, demonstrating simple tasks or perhaps even feeding or changing children. Howard argues that robotics need not lessen the human contact children get at daycare, since most of that comes through interacting with other children anyway.

Dan Schwartz, who directs a lab at Stanford dedicated to exploring ways of using technology in education, says the idea of using robots has potential, but says the hardware may not always be welcomed. “Children were often scared of the robot,” he says. “They were sort of alive but not alive. So all those issues with the ‘uncanny valley’ really show up with young kids.”

Howard says a robot such as Darwin could also work with elderly patients, reminding them to take their medication or to perform their daily exercises. In fact, a robotic seal called Paro, made in Japan, is already working in some nursing homes, where it helps reduce patients’ stress.

Maja Mataric, a professor at the University of Southern California who studies social robotics, says the big challenge is figuring out the dynamics of human-robot interaction. “We need to understand what users really need and what they want, which are not usually the same thing,” she says. “The challenges that stem from understanding people better, to create technologies that will stick, appear still to be some of the hardest.”